By Lorenzo Vercellati, Power BI Solution Architect at Lucient

“95% of presentations suck.” The foreword of the most famous book about presentations starts with this sentence. If we think about some reports we see every day, we can probably believe that too. This article aims to identify best practices to develop a more effective, efficient, and amazing data visualization technique.

Our process will develop along with four main points:

- Who is a data storyteller?

- What types of data visualization exist, and which is the goal for each of them?

- We will explore some visualization guidelines based on the rules of human perception.

- We will practice the main tips, tricks, and best practices about Power BI visuals.

You can think of your report as a Gothic Cathedral like Milan’s Duomo, Wien’s St. Stephen, or Paris’ Notre Dame: something great and complex, with a clear function, where all the aesthetic and structural elements have a specific role to play.

As in the Cathedral, as in your report, each distinct piece has inherent properties you can play with, but all choices must work for the whole.

Power BI reports: what matters most?

A Power BI report is founded on three main pillars:

- PowerQuery, where you load, clean, and transform your data sources

- Data Model & DAX, where you build relationships and measure, establishing the way your report works

- Visualizations, where you define how the user accesses data

Now, the Power BI Report results from the product of all three pillars, not the sum. This means that if the value of any of these pillars equals 0, the report’s value will also be 0.

- If your PowerQuery is poor, your data will be dirty or not optimized for your target.

- If your model does not respect modelization best practices, star schema and each DAX formula will become an Everest-like climb.

- If your visualizations are bad or too complicated to understand, users will abandon it.

Summing up: if your report does not work as a whole, it will be useless and soon forgotten.

Who is a data storyteller?

Now it’s time to focus on the visual pillar, trying to answer the first question: who is a Data Storyteller?

The data storyteller is a hybrid figure: half technician and half functional, half artist and half scientist.

If you neglect best practices, your report will be aesthetically gorgeous but difficult to use. On the other hand, if you do not take care of the visual aspect, it won’t be pleasant. In all two cases, people will not use your report, and all the work behind it will be lost.

So, our data storyteller must have two different types of skills: artistic and scientific. As artistic skills, we can list communication, innovation, and a good eye for design. Whereas for scientific skills, we can mention a good knowledge of how perception works and visualization best practices.

I cannot improve your artistic talent, which you probably have more developed than me, but I can help empower your visualization skills.

Data Visualization Types

We can start by clearing a very common misunderstanding among report developers: User Interface (UI) is not User Experience (UX).

A report could have a nice look, right color palette, titles and so on, but at the same time, it could be hard to use, not well-structured, or too crowded—think slicers on the right in a page and on the left in the next one.

Remember: you must work on UI, but always minding UX!

At the same time, reports should be not only useful but also AWESOME. People are used to amazing interfaces everywhere, so they expect the same at work.

First, we should determine what the user intends to do with our data visualizations to choose the best-fitting one.

There are three different types of data visualization in Power BI:

- Dashboards

- Reports

- Data Storytelling, also known as Presentations

Each type has its own properties, which you must be aware of to build a correct visualization. Not all approaches work for different visualizations.

The general definition of Dashboard is “a visual display of the most important information needed to achieve one or more objectives that have been consolidated on a single computer screen so that it can be monitored at a glance.”

No interactions: Dashboard is a one-shot visualization. The idea behind it is that you open it and you instantly apprehend all you need to understand (trends, KPIs, etc.).

“A visual display of the most important information needed to achieve one or more objectives that have been consolidated on a single computer screen so that it can be monitored at a glance.”

DEFINITION OF DASHBOARD

The information on a dashboard is usually a combination of text and graphics, emphasizing the latter. Graphical presentation, when handled expertly, can often communicate more efficiently and comprehensively than text alone.

So, now we know that the tiles of a Power BI dashboard are not related or drillable not because of a design issue, but in full compliance with the correct definition we have just learned.

Reports, instead, are interactive tools designed to drill data at multiple levels. When projecting a report, you must prepare the user to travel through the data.

A report is the most-fitting tool for Data Analysis, interacting between the different visuals and drills through multiple levels, from top to bottom. You may pitch and design, but the user will choose how to play the game.

Finally, presentations are where data storytelling skills can shine and show their full capabilities:

- You tell the story.

- You define the timeline.

- You can use more artifacts and tricks than in the reports.

Human Perception

When you project data visualization, you must consider how human perception works and sync your report accordingly.

You can find below an image of the visualization wheel, representing all the main characteristics a report could have. Every feature has a natural opposite, and all of them can be grouped into three main categories. Your goal is to find the right balance between all features included in a report.

Decoration vs. Functionality

Your report is a functional item. Data visualization is functional art. Decoration is fine, but never at the expense of functionality. Remember the cathedral example! A data visualization report should only be beautiful when its beauty can boost understanding in some way without undermining it in another.

Originality vs. Familiarity

It would be best if you found the balance between originality and familiarity. The secret is building something that contains understanding inside the novelty. Let me explain this concept better.

When you project a new report, you look for something original. Both for the user, because he deserves something that nobody else has, but also for yourself, because building the same report every time is comfortable but at the same time terribly boring.

Designing an original report is OK, but you also need to work on familiarity, using recurrent patterns to make the user experience more comfortable—an original layout but with recognizable patterns across the pages.

Density vs. Lightness

When you envision a report page, avoid filling it with lots of visuals, slicers, shapes, and colors. Just a few clear visuals should be enough. Bring multidimensionality into the user experience, building more levels of investigation using drill down and drill through.

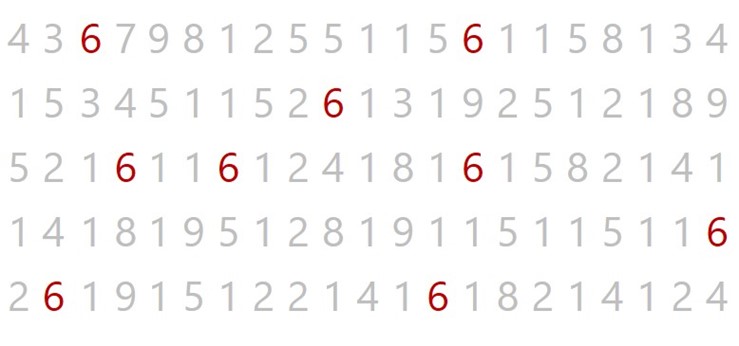

Look at the image below:

How many number sixes can you find in it? It’s not easy, because the human brain works on differences. But, with a little help, a difficult answer may become way easier.

This second table has the same sequence of numbers as the first one, but it’s much clearer. Keep in mind that the human brain works better on tone differences than on shape differences.

The Cleveland & McGill approach

In 1984, William Cleveland and Robert McGill created a catalog of visualization categories ordered by estimate type.

That same year, they published their seminal paper “Graphical Perception: Theory, Experimentation, and Application to the Development of Graphical Methods.” It remains a touchstone for data visualization researchers and practitioners, and academics have quoted it thousands of times.

Cleveland and McGill detailed the common cognitive tasks that happen when somebody reads a chart. They later evaluated how well subjects performed those tasks depending on the features the graph had.

The authors provide a general hierarchy for the types of data we most accurately understand:

- Position along a common scale (bar chart, dot plots)

- Positions along with non-aligned, identical scales (small multiples)

- Length, direction, angle (pie chart)

- Area (treemap)

- Volume, curvature (3-D bar charts, area charts)

- Shading, color saturation (heat maps, choropleth maps)

(Part II coming soon!)